Our Primary Years Newsletter helps young students to explore and make sense of the very latest real-world events and issues.

Alongside our Middle, Senior, and TOK newsletters, it enables schools to create a continuum of authentic critical thinking that will take students on a life-changing epistemological journey, and help them to become nuanced and courageous thinkers.

The primary years newsletter is coming…

We’ll be adding the primary years newsletter to our ACT continuum of learning at the end of 2024. But in the meantime, you can download a sample version of the newsletter here. If you are looking for resources to develop authentic critical thinking in your primary years students, you may be able to adapt our middle years resources found here.

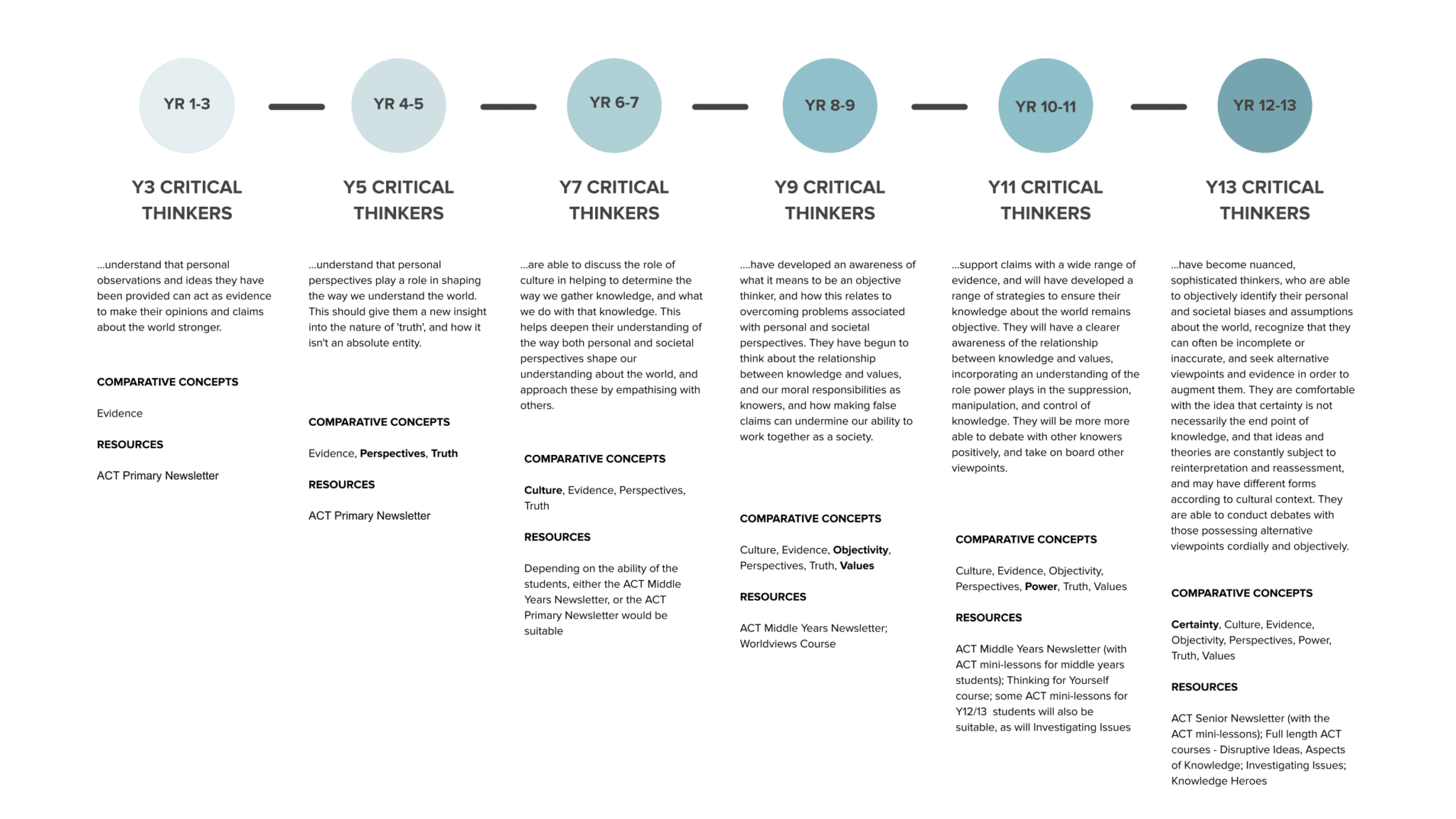

The ACT/TOK teaching and learning pathway

Placing ACT at the heart of what we do creates a learning pathway represented by the diagram below. We begin with resources for primary learners (now being introduced), move onto the middle years resources which we update each month, and culminate in either our resources for the TOK course, or if your students are following a different educational programme (such as A-Levels or the AP), senior ACT resources.

All our resources are incredibly flexible, and can be plugged into any educational programme. Deliver our full-length ACT courses in timetabled lessons, run our mini-lessons in PSE classes, use our extension resources such as Investigating Issues to fill your EPQ or HPQ slots, or offer your students our ‘Knowledge Journeys’ in optional extension classes outside of the usual timetabled day – it’s entirely up to you.

The 8 comparative concepts

We’ve selected 8 ‘comparative concepts’ that are of particular significance to us as authentic critical thinkers, and identified them in with a red font in the newsletter mini-lessons. Use the comparative concepts as as a cognitive framework to understand the world, a tool to compare and contrast different subject knowledge, and as focus points to generate research tasks and debates. Here are some of the questions they can prompt – can you think of others?

In which subject area are we able to make the most certain claims about knowledge and understanding? Why does this variance exist? Does language allow us to be more certain about knowledge? Can certainty bring disadvantages in terms of our understanding of the world?

How does the nature of the subject areas differ in different cultures? Do mathematics and science transcend cultural differences? Do the arts deal with culturally universal concepts? Does the way we understand the world depend on the language we speak?

Which subject is most and least affected by different perspectives? How do our religious and political perspectives shape our worldview? Do our perspectives determine our language use? What forms our perspectives, and should we seek to escape them?

How does power affect the way knowledge is produced within the subject areas? In what ways can language be used to consolidate power as ideas are communicated? How does political and religious power influence the way we understand the world?

Using the comparative concepts as a learning scaffold

The infographic below shows our cognitive aims for primary, middle, and senior learners, and the outcomes to aspire to by the end of each stage of their academic journey. We use the 8 comparative concepts as a scaffold to develop ACT skills, which you can find out more about here.

Students culminating ACT with TOK (rather than senior ACT learners), the comparative concepts become the 12 key concepts. The infographic also indicates resources that members have access to in order to achieve these learning aims. Click here to download a PDF of the infographic.

Join us to deploy the ACT continuum

Members have access to a huge range of ACT & TOK resources, including classroom-ready courses, TOK and ACT newsletters, TOK and ACT mini-lessons, Investigating Issues, TOK Padlets, 12 Key Concepts, and many more engaging, innovative resources!

Join in seconds via this page, and set up your whole school with a resource that will help you to become a hub of authentic critical thinking.